One of the charges made by certain un-canonical groups, and a few uneducated or belligerent parties in the Church, has been that the Divine Liturgy of the West was dramatically changed by the Normans after the invasion of Britain. I found this description from one of the major scholars of that representative Western rite of the Middle Ages (upon which the English services originate), Daniel Rock D.D., from his work "The Church of Our Fathers: As seen in St. Osmund's Rite for the Cathedral of Salisbury with dissertations on the belief and ritual in England before and after the coming of the Normans." 1849. A Catholic work - it has strong consonances with Orthodoxy. Dr. Daniel Rock was one of the English old Catholics (those who preserved the old English customs and tradition after the Reformation, contrary both to the Establishment - which was often Calvinist and Puritan, and contrary to the Jesuit missionary activity which sought to 'remake' Catholicism in that country into a new thing.)

"Protestant writers upon the history and antiquities of the Church in this country, have often allowed themselves to be easily misled into no small error concerning changes imagined to have been wrought by St. Osmund in our national ecclesiastical services.

Not for a moment must it be thought that this holy man either took away one smallest jot from the text of the liturgy for offering up the sacrifice of the mass, or altered a word of the ritual of administering any of the seven sacraments. Both the Sacrifice and the Sacraments were hallowed things, which the Normans looked upon with the like deep reverence and holy feeling as the Anglo-Saxons: for each nation's belief upon these articles of Christian faith was identical, flowing as it did out of the self-same well-spring of truth -- the apostolic see, the chair of St. Peter."

....

Now it should be asked: " In What did the Sarum ritual vary from that of Rome, and of the Anglo-Saxons?", the question is readily answered by replying, that the difference was neither much nor important. On comparing the Breviary, the Missal, and the Manual of Salisbury, with such of the service-books as have come down to us from Anglo-Saxon times, and those books now in use at Rome [1849], we shall find that they agree with one another almost word for word; so much so, indeed, as to show that St. Osmund did nothing more than to take the Roman liturgy as he found it at the time, ingraft upon it some slight unimportant insertions, and draw out its rubrics in such a way as to hinder the ordinary chances of falling into any mistakes about them from happening. He seems to have invented nothing of himself in these matters, but to have chosen out of the practices he saw in use around him, among the Anglo-Saxons here, and more especially among his own countrymen in Normandy; and it would appear he undertook nothing more than to arrange the church-offices in such sort that his clergy -- composed as they must have been of Normans and Anglo-Saxons -- might have one known uniform rule to lead them while going through their respective functions within the sanctuary, and their several duties amid their flocks."

....

Such, reader, are the chief though not all the beauties of our dear old Sarum rite, which, after all, was so very Anglo-Saxon in its leading features. To love those olden ways in which our fathers for ages trod, is what has been told us and taught us by some of the highest holiest men who have lived at different times and various places in God's one catholic everlasting Church. How St. Charles Borromeo strove and wrought successfully to keep up the liturgy and ritual as they were left by hid predecessor, the great St. Ambrose; how Cardinal Ximenes preserved, at Toledo, the Mozarabic service - are fact well known. ... The Holy See, nay the Church herself, has always acknowledged the lawfulness of keeping up local rites and praiseworthy customs in different countries. The council of Trent, Sess. XXIV., in its Decretum de Reformatione Matrimonii cap. i., says: - Si quae provinciae aliis, ultra praedictas, laudabilibus consuetudinibus et caeremoniis hac in re utuntur, eas omnino retineri sancta Synodus vehementer optat. For the holy See, and the Roman Congregation of Rites, Gavanti, than whom a more trustworthy witness could not be found, assures us that: - Proprios mores unaquaeque habet ecclesia et laudibiles consuetudines, quas non tolli a caeremoniali Romano, neque a rubricis Breviarii, saepius declaravit Sacra rittum Congregatio.

....

Between the Anglo-Saxon and the Sarum rite there was but small difference: this latter bore about it a strong sister likeness to the first, so that, while looking upon the one, we, after a way, behold both. In its features and its whole stature, we gaze, as it were, upon our fathers in their religious life; we read their ghostly annals, through a thousand years and more, as a Catholic people. It tells us what men and women, old and young, high and low, then did and must have done to have got for this land of England that sweet name, among the nations, of "The island of Saints." When we take a remembrance of this liturgy with us into the tall cathedral and the lowly parish church, those dear old walls that catholic hands built are again quickened into ritual life; we see the lighted tapers round the shrine, or circling about the Blessed Sacrament hung above the altar; we catch the chant, we witness the procession as it halts to kneel and pray beneath the rood-loft; to the inward eye, the bishop with his seven deacons and as many subdeacons, is standing at the altar sacrificing, and as he uplifts our divine Lord in the Eucharist, for the worship of the kneeling throng, we hear the bell toll forth slowly, majestically. From the southern porch-door, to the brackets on the eastern chancel wall for the B.V. Mary's and the patron saint's images, every thing has its own meaning and speaks its especial purpose, as intended by the use of Sarum. Can these rites never again be witnessed in England? They may. Let us hope then - let us pray for their restoration, so that England may once more gaze upon her olden liturgy; let us hope and pray that her children, in looking upon, may all acknowledge their true mother, and love and heed the teaching the while they study the ritual of the Church of our Fathers."

Postscript by W.H. Frere : "If the learned author were alive now and wished to find examples of the old English ways which were so dear to him he would have to go to the Churches of the establishment rather than to those of the Roman Catholic body." 1905.

Post-postscript: AFAIK, the English Sarum Use has only been done intermittently as experiments in our own time by Church of England clergy - and maybe once in Scotland by Roman clergy... and the Sarum pretty much is found only in use with the Western Rite Orthodox under ROCOR (and parts of it, or the heritage thereof amongst the Continuum and the Antiochian Western Rite - and still possibly with a few Anglo-Catholics or High Churchmen of the Church of England, and possibly within other churches in its Communion ?)

A bit more of the Very Rev. Dr. Daniel Rock's writing:

"The Anglo-Saxons were taught never to go beyond the threshold of a church without stirring up within themselves feelings of the deepest awe: for they were then treading hallowed ground: they were within the house of prayer - hard by the spot whereon the body of Christ was about to be consecrated - whereon the mysteries of his body and blood were being wrought; they were made aware that cherubim and seraphim hovered unseen about the altar, in noiseless, but most lowly worship; therefore was it becoming for man to awaken within his heart a reverential dread, and be there before the holy of holies, with eyes cast down to the ground, like the pious woman at the sepulchre, when, on going to seek the body of Jesus, they found it watched by an angel. Hence, too, they were told never to sit down during mass, unless weakness or bad health obliged them; and to hear it fasting.

Such feelings of awe for the spot on which was offered up the holy sacrifice, did not belong exclusively to our Anglo-Saxon forefathers, but may be seen, much before their time, acting upon other portions of the Church, both in the east and west, and have been fondly cherished ever since; nowhere, however, with more warmth than in our own England, while it was Catholic."

2.18.2005

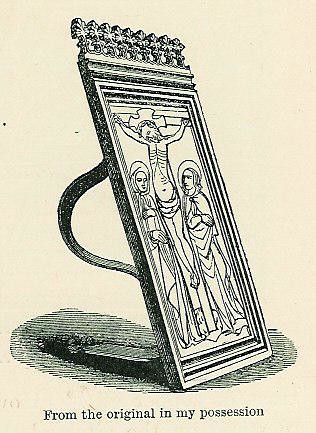

Pax-Brede

Here is a Western 'icon' that was used liturgically from at least the 13th c. (AD 1200's) for the Kiss of Peace.

From Daniel Rock's "The Church of Our Fathers", 1849:

"Instead of the clerk's cheek, the priest kissed the figure of our Blessed Lord, painted on a small piece of wood, or graven on a plate of copper, set in a frame, with a handle behind, as is shown in this cut. So shaped, it could easily be carried about among the people by the clerk, in his left hand; and, after each kiss bestowed upon it, wiped with a little napkin which he held for that purpose in his right hand. The earliest mention anywhere of such a ritual appliance, is to be found among this country's ecclesiastical enactments, in which it is called "osculatorium," "asser pacis," "tabula pacis."28 Its more common name was "pax-brede," which at once told its liturgical purpose, and of what material it happened, at first, to be generally made. Afterwards, gold, silver, ivory, jewels, enamel, and the most beautiful workmanship, were bestowed upon it; though, for poor churches, it still continued to be made of wood, or at most, of copper gilt.

--------------

28 Among other sacred things to be found by the parishioners for their church, according to the statutes of Archbishop Walter Gray, for his province of York (A.D. 1250), was "osculatorium." (Wilkins, Concil., i. 698.) In like manner the synod of Exeter (A. D. 1287) decreed there should be "asser ad pacem" (ibid., ii. 139), and the council of Merton (A.D. 1305), "tabulas pacis ad osculatorium" (ibid., 280). "

The pax-brede, along with the Eulogiae (holy bread) was withheld from hardened sinners first among items barred from those excommunicated. The Gospel was also used as such at High Masses in Cathedrals (like the Gospel at Byzantine Orthros.)

Also from Daniel Rock D.D. Canon of the English Chapter (Roman Catholic):

"In going to meet, for the first time, that pagan king, St. Austin and his holy fellow-labourers went forward carrying for a banner a silver cross and the image of our Lord and Saviour painted on a board.... The use of images and pictures in churches, is well defended by this great Anglo-Saxon father [Venerable Bede] in another part of his writings; and he shows that as under the Old, so in the New law, the employment of images is quite allowable: [referring to the Venerable Bede's commentary on Exodus]... Upon the principle that the Church is the teaching-house of holiness, therefore the walls themselves about the earthly building should speak of heaven... upon this principle was it that the Anglo-Saxons strove their best to get the images of Christ, of his ever-virgin mother, of the apostles and of the saints, and to look for artists who might paint subjects from holy writ, to adorn the walls of their churches.... On going, then, into an Anglo-Saxon minster, here and there might be seen, done in bronze, or some one or other of the more valuable metals, representations of the life and miracles of our divine Redeemer. But in those places where it could be procured, the whole inside of the church was covered with paintings of the saints, and illustrations of passages of holy writ. "

See: PaintedChurch.org for surviving examples.

From Daniel Rock's "The Church of Our Fathers", 1849:

"Instead of the clerk's cheek, the priest kissed the figure of our Blessed Lord, painted on a small piece of wood, or graven on a plate of copper, set in a frame, with a handle behind, as is shown in this cut. So shaped, it could easily be carried about among the people by the clerk, in his left hand; and, after each kiss bestowed upon it, wiped with a little napkin which he held for that purpose in his right hand. The earliest mention anywhere of such a ritual appliance, is to be found among this country's ecclesiastical enactments, in which it is called "osculatorium," "asser pacis," "tabula pacis."28 Its more common name was "pax-brede," which at once told its liturgical purpose, and of what material it happened, at first, to be generally made. Afterwards, gold, silver, ivory, jewels, enamel, and the most beautiful workmanship, were bestowed upon it; though, for poor churches, it still continued to be made of wood, or at most, of copper gilt.

--------------

28 Among other sacred things to be found by the parishioners for their church, according to the statutes of Archbishop Walter Gray, for his province of York (A.D. 1250), was "osculatorium." (Wilkins, Concil., i. 698.) In like manner the synod of Exeter (A. D. 1287) decreed there should be "asser ad pacem" (ibid., ii. 139), and the council of Merton (A.D. 1305), "tabulas pacis ad osculatorium" (ibid., 280). "

The pax-brede, along with the Eulogiae (holy bread) was withheld from hardened sinners first among items barred from those excommunicated. The Gospel was also used as such at High Masses in Cathedrals (like the Gospel at Byzantine Orthros.)

Also from Daniel Rock D.D. Canon of the English Chapter (Roman Catholic):

"In going to meet, for the first time, that pagan king, St. Austin and his holy fellow-labourers went forward carrying for a banner a silver cross and the image of our Lord and Saviour painted on a board.... The use of images and pictures in churches, is well defended by this great Anglo-Saxon father [Venerable Bede] in another part of his writings; and he shows that as under the Old, so in the New law, the employment of images is quite allowable: [referring to the Venerable Bede's commentary on Exodus]... Upon the principle that the Church is the teaching-house of holiness, therefore the walls themselves about the earthly building should speak of heaven... upon this principle was it that the Anglo-Saxons strove their best to get the images of Christ, of his ever-virgin mother, of the apostles and of the saints, and to look for artists who might paint subjects from holy writ, to adorn the walls of their churches.... On going, then, into an Anglo-Saxon minster, here and there might be seen, done in bronze, or some one or other of the more valuable metals, representations of the life and miracles of our divine Redeemer. But in those places where it could be procured, the whole inside of the church was covered with paintings of the saints, and illustrations of passages of holy writ. "

See: PaintedChurch.org for surviving examples.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)